According to the dictionary, to belch is “to bring forth wind noisily from the stomach.” The interchangeable word “burp’ does not appear in some dictionaries, but it seems to mean, “cause to belch.”

Belching after a large meal is a normal, necessary venting of air from the stomach. In some societies it is a gesture of appreciation to the host.

Nevertheless, for some people, belching is a serious and difficult matter. They are plagued by sudden attacks of belching which is both intrusive and embarrassing. It may cause concern that the gas or air that is belched originates in the “stomach,” and that it is an indication of an underlying gas-producing disease.

Fortunately, that is rarely the case, and a doctor’s assessment should be reassuring. Indeed, all available evidence points to swallowed air as the source of the stomach gas and the perceived need to bring it up. This process is called aerophagia.

Aerophagia

Air swallowing is normal, although it contributes no discernible benefit. Newborns have no gas in their intestines until they draw their first breath. Subsequently air appears progressively down the gut. Normally, the esophagus contains some swallowed air. In a disorder called achalasia, where the valve at the lower end of the esophagus cannot relax, the stomach contains no gas at all.

During inhalation, the pressure in the esophagus falls, drawing in air. Deliberate inhalation against a willfully closed windpipe draws even more air into the esophagus.

Commonly, aerophagia is an unwanted habit in those who repeatedly burp, sometimes in response to a sense of abdominal bloating (but belching and abdominal bloating often occur independently).

When a person swallows saliva, about 5 mL of air is ingested, and more is ingested during a meal. We accumulate more intestinal gas when nervous than when relaxed. Other mechanisms include thumb sucking, gum chewing, rapid eating, and poor dentures.

Stomach gas has the same composition as the atmosphere and the volume increases about 10% when heated by body temperature. Carbonated drinks and antacids reacting with hydrochloric acid produce carbon dioxide and traces may diffuse from the blood. However, the stomach usually rids itself promptly of gas. For example, air forced into the stomach during a stomach examination (endoscopy) often appears in the rectum within 15 minutes.

Almost all stomach gas is ingested in this way. Exceptions include bowel obstruction or a fistula (opening from the colon to the stomach as a result of disease). This directs colon gases into the stomach. Occasionally, paralysis of the stomach permits bacteria to grow and produce hydrogen.

When the stomach is distended by a meal, the stretched muscle results in feeling of fullness (satiety) or sometimes discomfort. A satisfying belch may ease this feeling.

The ability to tolerate stomach distension varies, and some individuals seem unduly sensitive. If release of gas relieves the distended feeling, even transiently, a cycle of air swallowing and belching may be established.

People with gastroenteritis, heartburn, or ulcers swallow more frequently, but the ensuing belch is probably a counter stimulus of no lasting benefit. The swallow-belch cycle may continue long after the original discomfort is forgotten.

Features of belching

Supine Position

Expelling gas is important, especially for people unable to do so. When the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is reinforced by anti-reflux surgery, belching may be impossible.

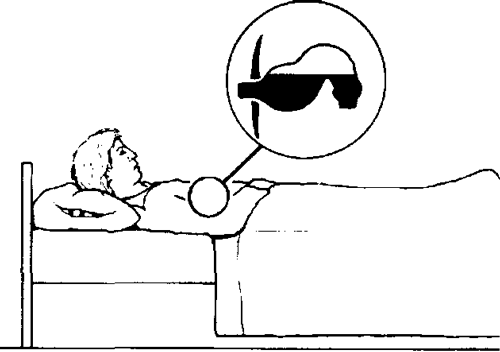

Swallowed air is lighter than food and most reaches only the esophagus. However, bedridden patients such as those recovering from surgery may trap air in their stomachs, becoming very uncomfortable. In the supine position (lying face upward) gastric contents seal the gastroesophageal junction so that air cannot escape.

Relief is achieved by lying face downward, in the prone position. Sometimes sleeping on the right side favors a therapeutic belch.

Repetitive belching is neither normal nor useful. While a person may insist that his or her stomach is producing large amounts of gas, in reality, air is repeatedly drawn into the esophagus and belched in the manner described above. A little may even reach the stomach.

Most sufferers are relieved to have their air-swallowing habit pointed out. Quitting is often difficult. Repeated and intractable belching has been termed eructio nervosa.

Treatment

A physician should take a careful history and examine the belching patient’s abdomen and mouth to be sure no other disease exists. Occasional belching, especially if it is after a meal is normal and requires no treatment.

Those who feel they belch excessively should understand the relationship of belching to air swallowing as described above. After a doctor’s examination, it is reassuring to learn there is no underlying disease, and that there are no consequences beyond possible embarrassment.

Eating slowly allows time for air to be moved along the intestine, or absorbed. Excessive chewing or sucking should be avoided by choosing food that is easily chewed.

Relaxation techniques may be of benefit. Some good results are reported with hypnosis, but there are no scientific studies to support any treatment.

Learn more about using relaxation in coping with GI disorders

Adapted from IFFGD Publication #511 by W. Grant Thompson, MD, FRCPC, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada